January 01 2015

Example 1: In this case the defendant was told in interview that his shoes matched a mark at the scene of a burglary and was asked to account for this. The SFR1 actually reported that the defendant and another man’s shoes had been compared to the mark and that both had the same pattern. No further evaluation had been made. We were asked to conduct a full comparison with both pairs of shoes and found that whilst both pairs had the same pattern and size, the second man’s shoes matched the scene mark in terms of its wear, whereas the defendant’s did not.

Example 2: The defendant’s shoes had been submitted together with marks from a warehouse floor, to an expert within a Police Identification Unit. The pattern and size were both common and there was nothing particularly characteristic about the wear. Given this information, the ‘match’ had been correctly reported as providing ‘limited support’. However, during our examination it became apparent that there had been several other suspects with the same type of shoes. Screening had shown that one of these other pairs of shoes matched one of the scene marks better than the defendant’s, the other marks not favouring either pair. This second pair of shoes had never been submitted for a full evaluation.

Example 3: The defendant was charged with assault. Several people were involved in the attack and a number of pairs of shoes seized from the suspects (including the defendant’s). There were bruise marks on the injured party’s face. It was not clear if this was a single mark or multiple marks. Part of this area recorded a pattern which was similar to the defendant’s shoes; however, if the mark was a single mark, it could not have been made by these shoes. There was no record that any of the shoes from the other suspects had been examined.

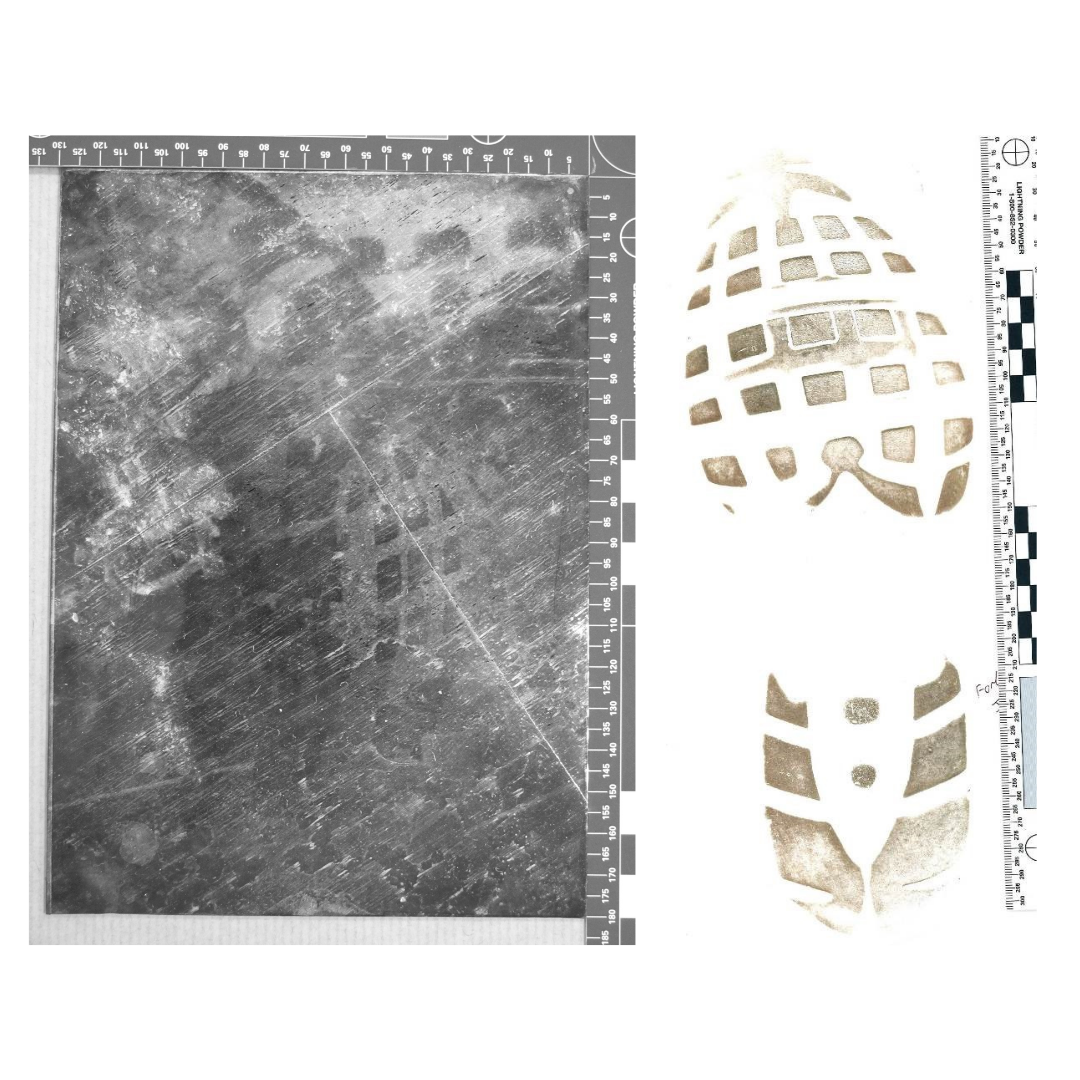

Example 4: The defendant was told in interview that a mark matching his shoes was found on a door where it had been kicked. He was asked to account for this. There was no forensic footwear mark report in the case papers and we were asked to examine the evidence. Our examinations clearly showed that the mark was of an entirely different pattern from the defendant’s shoes (Figure 1), and was on the floor at the scene and not on the door as alleged.

Figure 1 - Test mark from defendant's shoe (top), mark from scene (middle) and an example of the actual pattern in the scene mark (bottom)

Example 5: The defendant was arrested close to a scene and the shoes he was wearing seized. The solicitor noted that a mark had been lifted from the scene, but no report or SFR1 issued. On making enquiries the CPS replied that a footwear mark analyst had told them that there was nothing of significance in the scene mark so no work had been carried out. We were asked to examine the mark and found it was clearly visible and of a different pattern from the defendant’s shoes (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Test mark from defendant's shoe (left) and mark from scene (right), printed to the same scale

Example 6: The defendant was alleged to have been the driver of a stolen vehicle. He stated that he had been the front seat passenger in the vehicle. A footwear mark was lifted from the panel in front of the passenger seat, but no comparison made to the defendant’s shoes. When we asked to examine these items we were refused permission by the police. They said that the mark on the lift had degraded so much that there was nothing left to see. We successfully argued that we should still examine the lift so we could draw our own conclusions, and attended the police headquarters to do this. On arrival we were told that the lift had deteriorated to such an extent that it had been destroyed. We produced a critical report arguing that we should have been able to assess this for ourselves, and shortly afterwards the lift was ‘found’ and sent to our laboratory for examination. The lift bore a clear mark which corresponded to the defendant’s shoe, supporting his account.